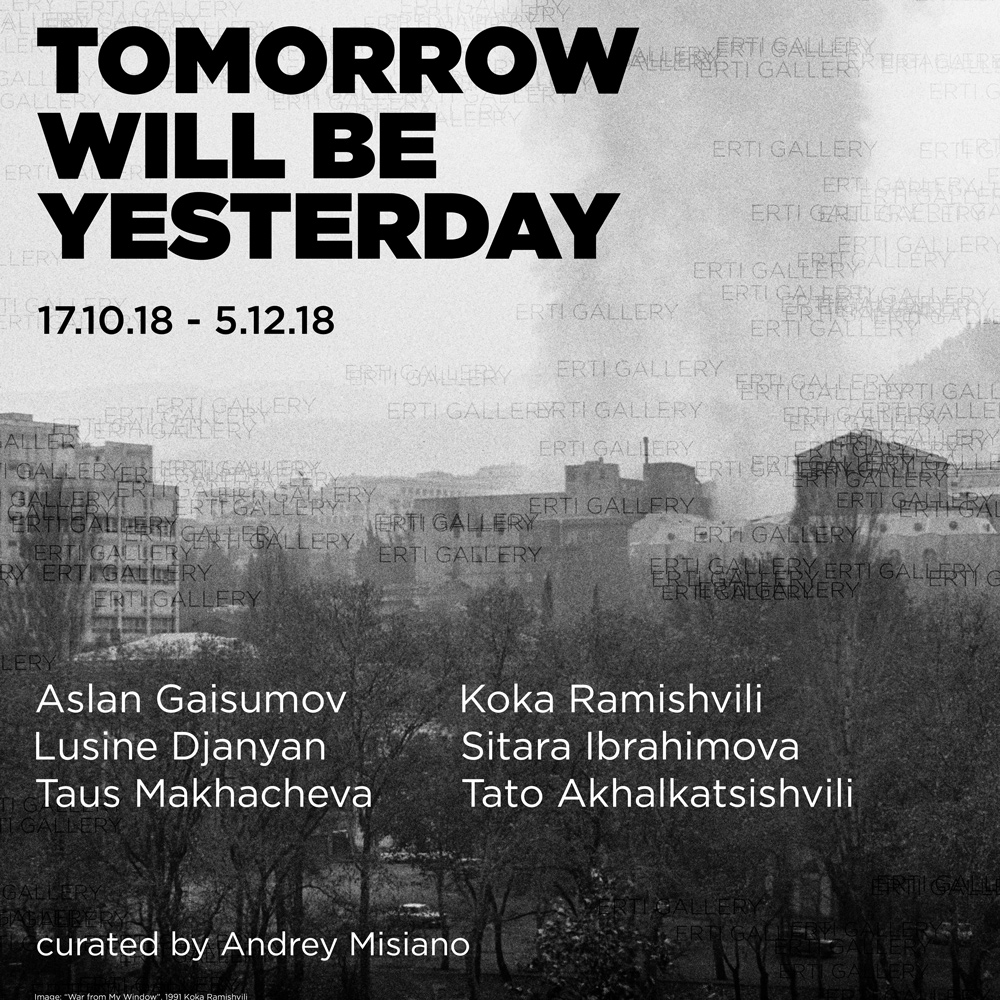

Tomorrow Will Be Yesterday | Group Show

Tomorrow Will Be Yesterday

Curator: Andrey Misiano

ERTI Gallery presents the exhibition Tomorrow Will Be Yesterday, which is based on a study of the work of a broad group of artists whose origins are inextricably tied with the Caucasian region. This is the third in a series of exhibitions1 devoted to the contemporary art scene in the Caucasus. The range of themes of the first two exhibitions included the loss of home, forced migration, the politics of identity, and history after the “end of history.” The present exhibition mostly focuses on history, geopolitics and ethnic strife in the region. It examines the experience of individuals and whole nations confronted with historical cataclysms and change.

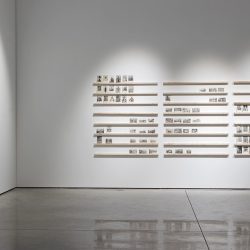

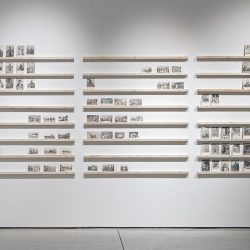

The exhibition opens with Types du Caucase (2013 — present) by the Dagestani artist Taus Makhacheva. This work is a collection of postcards from the Russian Empire depicting different Caucasian tribes and religious groups according to all the rules of exoticization. It is noteworthy that the original captions were written in the two languages (Russian and French) spoken by the elite of the time.

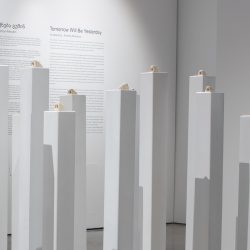

The works of the Swedish-based artist Lusine Djanyan and the Azerbaijani artist Sitara Ibrahimova examine the arguably biggest (and still unresolved) ethnic conflict in the Caucasus: the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute. Originating in the Early Modern Period, this conflict flared out twice in the 20th century during the disintegration of the Russian Empire and the breakup of the USSR. Djanyan’s Ires (2014) consists of sewn-together blankets with images of several genera- tions of the artist’s family, alluding to the hot phase of the conflict during the Perestroika. The “ires” is a special cut of a precious fabric that is applied to the upper part of a blanket. Many Ar- menian refugees that left Azerbaijan in 1988 wrapped their belongings in a bundle made of such fabric. Ibrahimova’s photo series Lost in Karabakh (2009 — present) is also connected with the material world of people that went through the catastrophe of war. Ibrahimova photographs the belongings of people that disappeared during the conflict. Rather than imposing a specific plot or complex narrative on the viewer, this series of images simply shows a quiet world of things that will never serve their owners again. Tato Akhalkatsishvili’s new work “Tomorrow will be yesterday” 2018, treats a special type of conflict that takes place in human memory. Although his goal is to generalize collective images, he starts with his personal memories of a childhood, of a country that has long since disappeared (and perhaps had never existed in the first place), and of the areas and collisions of history that have still not been evaluated in a clear-cut fashion and continue to be revised and discussed.

The disintegration of the Soviet Union led to the outbreak of several armed ethnic conflicts in the Caucasus and Central Asia. The most severe and protracted among them was the Chechen War. At the exhibition, the Chechen artist Aslan Gaisumov presents his collection of Postcards (2015) issued during the short period between the two wars during the existence of independent Ichkeria (1996-1999). They have one remarkable feature in common: instead of scenic landscapes or brightly lit skyscrapers that are usually depicted on postcards, they show views of war-ravaged Grozny.

In addition to ethnic conflicts on the territory of the former USSR, a civil war broke out in Georgia in 1991-1992. At the peak of the fighting, Koka Ramishvili photographed the skirmishes in the center of Tbilisi from his window. The video project War from My Window shows the war in an intentionally quiet and subdued way, highlighting the mix of the eternal and the temporal that marked the moment. The work contains no national, territorial or political messages, simply depicting the same landscape during twelve days of (invisible) war.

Makhacheva’s Landscape thematically unifies the exhibition without touching upon any of the sore spots of the history of countries and republics. Introducing the dimension of the landscape into the exhibition in a witty manner, it consists of a spatially arranged series of noses of different Caucasian peoples. There are several folk sagas in Dagestan, about men, who have lost their noses. In the Avar language the word “мerlep” means both “mountain” and “nose”, demonstrating how strongly the mountain-dwellers identify with the mountains. Together they symbolize the Greater Caucasus mountain range — a territory whose history has been troubled for over two thousand years already.

1 Untitled… (Native Foreigners), Garage Museum, Moscow, July 7 — August 10, 2014; Life from My Win- dow, Laura Bulian Gallery, Milan, October 19, 2017 — January 26, 2018.